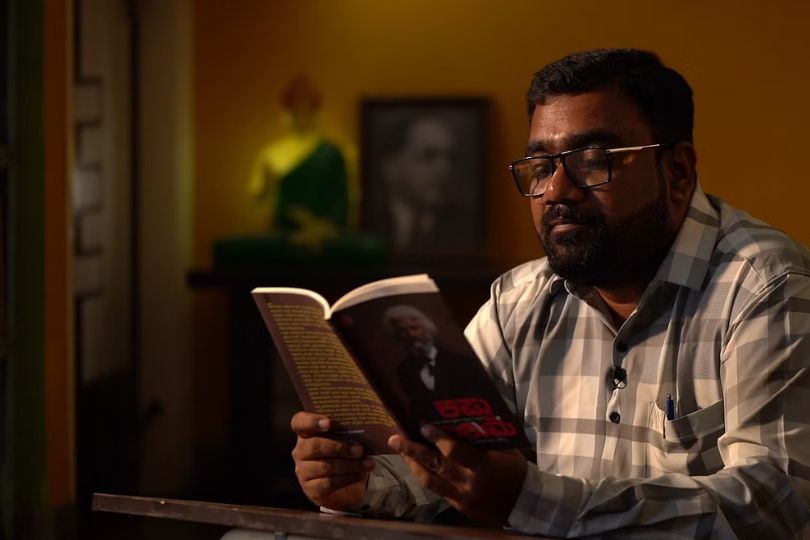

Literature Has a Strong Connection to Dalit Identities

Explore Dalit experiences through Vikas R Mourya's writings. A Kannada writer and Ambedkarite activist, his work delves into caste, identity, and social justice in post-liberalised India.on Jan 02, 2024

Vikas R Mourya, who grew up in close proximity to social movements and activist groups, investigates the lived experience of a new generation of Dalits in his literature.

In the title story of Kannada writer and activist Vikas R Mourya's (42) short story collection, Neelavva, a Dalit woman gets disabled after being raped in the hamlet by a privileged caste man. At the start of the story, you could be forgiven for thinking it was one of the hundreds of atrocity narratives based on caste, which clearly divides the protagonists into victimised and oppressors.

Unlike the dominant narrative, Vikas appears to have correctly identified the intersectional nature of our social identities — religion, class, caste, gender, and so on – and how these influence where we stand on the oppressed-oppressor binary at any particular time. In Neelavva, the victim's son rapes the perpetrator's daughter to avenge his mother, who shouts in sorrow after realising what he has done, "All of you are the same!"

"Patriarchy lives even inside of me," says Vikas, who identifies as an Ambedkarite. "There is male dominance even among Dalits." We must overcome this."

Aside from Neelavva, his literary output includes a collection of nonfiction writing (Chammatige), a children's book (Jai Bheem), and four translations (Kappu Kulume, Ambedkar Jagattu, Ambedkar Siddhantha, and Savitribai mattu Naanu), the last of which was done in partnership with his wife, Kesthara. Kesthara, the daughter of Dalita Sangharsha Samiti's N Venkatesh, is also a writer. She pushed him to compose Buddhana Belaku, a parody of Buddha and his teachings. The show is now touring Karnataka and will soon arrive in Bengaluru. "On Naraka Chaturdashi, when India was playing in the World Cup, 400-500 people came to watch Buddhana Belaku," Vikas cites as an example. "The entire hall of Ta Ra Su Rangamandira was filled with families!"

His writings have been lauded for delving into the lived experiences of a new generation of young Dalits growing up in post-liberalised India. As an activist, he has taken part in campaigns such as Chalo Udupi (2016) against caste abuses in the district.

"Vikas is important because he searches for the roots of Dalit movements that were prevalent in the 1970s and 1980s," writes Du Saraswathi, a writer, theatre artist, and activist. "For Vikas, writing and social movements are not different from each other."

"In the works of those who are close to social movements, there is a danger of literature becoming just slogans," says poet-activist Hulikunte Murthy, a friend of Vikas'.

"It takes a different kind of ability to imbibe Ambedkarite art within literature and Vikas has that."

Becoming an Ambedkarite

Vikas grew up in close proximity to social movements and activist groups as the child of Dalit parents from two different subcastes. In fact, his parents were married in Kolar by the Dalita Sangharsha Samiti (DSS), an association created to speak for all Dalits.

N Venkatesh, one of the organization's founders, is Vikas' maternal uncle and a role model. As a young youngster growing up in KR Pete, Mandya, he was so intimately involved with DSS activities.

However, at this age, B R Ambedkar was only a photograph in the DSS booklets he used to distribute in public. When he was studying for the II PUC supplemental test, he came to come across volume 3 of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar's Writings and Speeches in his uncle's bag.

"At the time, my English was terrible," Vikas recalls. "So, I read the book with the help of a dictionary."

This encounter with Ambedkar's Vol 3 will lead even this follower of Hindu Gods down the path of Ambedkarism. Later, his affiliation with the Bahujana Vidyarthi Sangha (BVS) introduced him to SC/ST/OBC politics.

Today, you may mention a topic and he will tell you which volume of Ambedkar's writings to consult. This is unusual in Karnataka, according to Hulikunte Murthy: "There has always been a gap in understanding Ambedkar, as we have read him through translation," he says. "But, since Vikas has read them in English, he can capture the real meaning and essence behind Ambedkar's words."

Based on Social Reality

Growing up in a middle-class, socially conscious household in locations like KR Pete and Mysuru, the practice of untouchability was less visible. The undercurrents of caste were evident, but suppressed. That changed when he was hired as a teacher at a village in Ballari's Sandur taluk. He saw how blatantly untouchability was practiced when he was 24 years old and fresh out of a BEd college.

"I was struck by how my community was seen and treated there," Vikas said. "That's when I realised I should use the medium of poetry and literature to express the pain I was feeling inside me and could not do anything about."

His works fluidly transition from rural to metropolitan settings, yet caste pushes its characters to bear everything hurled at them, often rendering them helpless.

His nonfiction writings, on the other hand, are clear and assertive, with no sense of hesitancy or indecision. There is also a lot of self-criticism when it comes to the splinters within the Dalit movement.

In Karnataka, the Dalit castes are divided into SC-Left and SC-Right, with the former historically oppressed more than the latter. Even within DSS, right-hand castes like Holeyas have had considerably better representation than Madigas, who are SC left, according to Murthy.

"Vikas has tried to bridge this divide, even so far as to convince the leaders of DSS by describing the necessity of uniting people of all SC castes vividly."

This was one of several reasons why Aharnishi Prakashana published Akshatha Humchadakatte twice: "I wanted to publish him because he writes as a critical insider from within the community," Akshatha said. "He has clarity of thought and is straightforward, rarely mincing words."

The Dalit claim Vikas is well aware of the literary tradition of which he is a part, and is quick to cite K Ramaiah, Devanuru Mahadeva, KB Siddaiah, Siddalingaiah, and others as people he read and listened to as a child. The character of progressive politics has also shifted, with a renewed emphasis on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, with most literary festivals now incorporating at least one caste panel in their schedule.

However, having one's identity reduced to their caste can be unsettling at times. In one of his interviews with the Indian Cultural Forum, Dr. Siddalingaiah jokes, "If not a famous Kannada poet, they should have printed a famous Dalit poet."

Vikas, unlike past generations, welcomes the label: "We are proud to call ourselves Dalit poets and to produce Dalit literature."In fact, he asks that the mainstream make no concessions because, regardless of recognition or invitations, "we will continue to write and we will make you read what we write."

In this regard, he is already working on a book about reservation policies. This book is the culmination of more than six years of research. Likewise, he is working on a book titled "Dalit Files."

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.